"'They're such beautiful shirts,' she sobbed, her voice muffled in the thick folds. 'It makes me sad because I've never seen such -- such beautiful shirts before'" (The Great Gatsby, 92).

Haha, what? This whole reunification scene in chapter five is very interesting. Hmm, maybe "awkward" is a better word.

First of all, Gatsby acts like a teenager when he has Jordan and Nick set him up with Daisy without actually talking to her. Then, after Nick says he will arrange a meeting between Gatsby and Daisy, Gatsby responds by offering Nick a job. Then, the day of the meeting, Gatsby gets stage fright, and when Nick walks into his house bringing Daisy, Gatsby had fled the living room. And then he decides to make it even more awkward by knowing offhand that they hadn't seen each other for "five years next November" (87). Poor Nick has to give him a pep talk!

Then, after about half an hour, Nick returns to the living room to see Daisy's face "smeared in tears" and Gatsby "glowing" with joy (89). "After his embarrassment and his unreasoning joy he was consumed with wonder at her presence" (91-2). They get absorbed in each other's materialism when Daisy cries over his nice shirts and then adores his yacht. Perhaps the most entertaining part is when Nick becomes their chaperon. "I tried to go then, but they wouldn't hear of it; perhaps my presence made them feel more satisfactorily alone" (94).

As I finish the first half of the novel, I'm not quite sure where this relationship is going to head. It has weird foundations in mutual wealth and materialism, and they remember each other fondly from a brief meeting five years ago. I mean, in my mind, there's no way this is going to turn out well for either one of them.

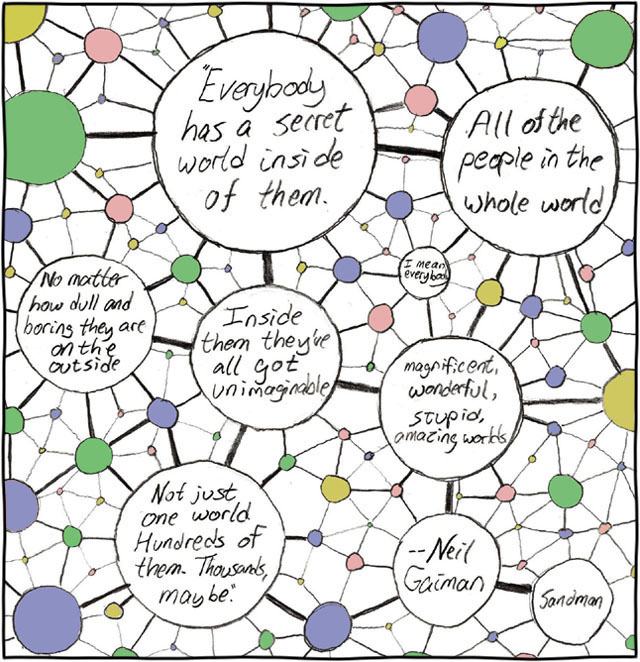

Speaking of Gatsby's deepest secrets, here's an xkcd picture I like. I think I used it for Never Let Me Go, but it really fits the wealthy characters in this novel, too. Behind Gatsby's countenance is his crazy longing for Daisy Buchanan. I like him -- he seems more modest and casual than the other wealthy characters, but his obsession with Daisy is a little creepy, and there's no doubt that he's materialistic, as well.

Showing posts with label characterization. Show all posts

Showing posts with label characterization. Show all posts

Saturday, April 21, 2012

Gatsby: Introducing the Rich People

"I lived at West Egg, the -- well, the less fashionable of the two, though this is a most superficial tag to express the bizarre and not a little sinister contrast between them" (The Great Gatsby, 5).

The two dueling settings in The Great Gatsby are East Egg and West Egg. From how Nick describes the two locations, I've decided that East Egg is more fashionable, condescending, lazy, and rich. Let's talk about the Tom and Daisy Buchanan, whom Nick visits in East Egg.

Tom Buchanan is "enormous," "supercilious," "wealthy," and a college football player (5-7). Nick hilariously calls him "one of those men who reach such an acute limited excellence at twenty-one that everything afterward savors of anticlimax" (6). Oh, and he's having an affair with some materialistic married girl named Myrtle.

If I had to choose one word to describe Daisy Buchanan, it would be "insecure." When her daughter was born, Daisy said, "'I'm glad it's a girl. And I hope she'll be a fool -- that's the best thing a girl can be in this world, a beautiful little fool'" (17). That insecurity of hers is clarified quite a bit in chapter four when Jordan tells Nick about the night before Daisy's wedding: "'Tell 'em all Daisy's change' her mine. Say: "Daisy's change' her mine!"'" (76). Her relationship with Tom is very weak, but she really hits it off with Mr. Gatsby.

I've got to finish off with a few more ironies I enjoyed. Tom says, "'Don't believe everything you hear, Nick'" shortly before his wife says, "'We heard it from three people, so it must be true'" (19). I also liked Tom's racist comment that "'we've produced all the things that go to make civilization'" as he lazily enjoys a luxurious meal in a lavish house in a fashionable area, none of which he actually worked for himself (13).

The two dueling settings in The Great Gatsby are East Egg and West Egg. From how Nick describes the two locations, I've decided that East Egg is more fashionable, condescending, lazy, and rich. Let's talk about the Tom and Daisy Buchanan, whom Nick visits in East Egg.

Tom Buchanan is "enormous," "supercilious," "wealthy," and a college football player (5-7). Nick hilariously calls him "one of those men who reach such an acute limited excellence at twenty-one that everything afterward savors of anticlimax" (6). Oh, and he's having an affair with some materialistic married girl named Myrtle.

If I had to choose one word to describe Daisy Buchanan, it would be "insecure." When her daughter was born, Daisy said, "'I'm glad it's a girl. And I hope she'll be a fool -- that's the best thing a girl can be in this world, a beautiful little fool'" (17). That insecurity of hers is clarified quite a bit in chapter four when Jordan tells Nick about the night before Daisy's wedding: "'Tell 'em all Daisy's change' her mine. Say: "Daisy's change' her mine!"'" (76). Her relationship with Tom is very weak, but she really hits it off with Mr. Gatsby.

I've got to finish off with a few more ironies I enjoyed. Tom says, "'Don't believe everything you hear, Nick'" shortly before his wife says, "'We heard it from three people, so it must be true'" (19). I also liked Tom's racist comment that "'we've produced all the things that go to make civilization'" as he lazily enjoys a luxurious meal in a lavish house in a fashionable area, none of which he actually worked for himself (13).

Gatsby: Introducing Nick Carraway

"'Whenever you feel like criticizing any one,' he [my father] told me, 'just remember that all the people in this world haven't had the advantages that you've had'" (The Great Gatsby, 1).

I haven't quite decided whether I should endow Nick Carraway or Mr. Jay Gatsby with the title of "protagonist" quite yet, but Nick is certainly the narrator. This quote from his father -- the idea that "a sense of the fundamental decencies is parcelled out unequally at birth" -- is central to Nick's character. Although the vastly wealthy people around Nick don't behave very respectably, our narrator reserves judgment, which opens him up to the deep secrets of other characters like Mr. Gatsby.

I really like Nick's character, partly due to his modesty. Around his wealthy acquaintances, Nick admits, "'You make me feel uncivilized, Daisy.'" Calling himself uncivilized among a house full of extremely hypocritical, racist, materialistic, and impulsive characters (more on that in my next post) is modest, in addition to being ironic. I'm very fond of Nick's voice; his sarcasm is very witty and thoughtful, and it goes way over the heads of the Buchanans. "'Do you want to hear about the butler's nose?' 'That's why I came over to-night'" (13).

One of Nick's iffy spots would probably be his incredulity. "He [Gatsby] looked at me sideways -- and I knew why Jordan Baker had believed he was lying" (65). At one point, he was so disbelieving that he had to restrain laughter at Gatsby's story. But everything becomes true to Nick when he sees physical proof: Gatsby's war medal and picture from Oxford. In my opinion, even his skepticism is likable -- in Nick's defense, he's around a bunch of secretive wealthy people, so being suspicious is no crime.

Fun fact: this Christmas, while Leonardo DiCaprio will be portraying Mr. Gatsby, Tobey Maguire will be taking the role Nick Carraway in The Great Gatsby! Your friendly neighborhood Spiderman.

I haven't quite decided whether I should endow Nick Carraway or Mr. Jay Gatsby with the title of "protagonist" quite yet, but Nick is certainly the narrator. This quote from his father -- the idea that "a sense of the fundamental decencies is parcelled out unequally at birth" -- is central to Nick's character. Although the vastly wealthy people around Nick don't behave very respectably, our narrator reserves judgment, which opens him up to the deep secrets of other characters like Mr. Gatsby.

I really like Nick's character, partly due to his modesty. Around his wealthy acquaintances, Nick admits, "'You make me feel uncivilized, Daisy.'" Calling himself uncivilized among a house full of extremely hypocritical, racist, materialistic, and impulsive characters (more on that in my next post) is modest, in addition to being ironic. I'm very fond of Nick's voice; his sarcasm is very witty and thoughtful, and it goes way over the heads of the Buchanans. "'Do you want to hear about the butler's nose?' 'That's why I came over to-night'" (13).

One of Nick's iffy spots would probably be his incredulity. "He [Gatsby] looked at me sideways -- and I knew why Jordan Baker had believed he was lying" (65). At one point, he was so disbelieving that he had to restrain laughter at Gatsby's story. But everything becomes true to Nick when he sees physical proof: Gatsby's war medal and picture from Oxford. In my opinion, even his skepticism is likable -- in Nick's defense, he's around a bunch of secretive wealthy people, so being suspicious is no crime.

Fun fact: this Christmas, while Leonardo DiCaprio will be portraying Mr. Gatsby, Tobey Maguire will be taking the role Nick Carraway in The Great Gatsby! Your friendly neighborhood Spiderman.

Sunday, February 26, 2012

Let's talk about Tom!

"But I'm not patient. I don't want to wait till then. I'm tired of the movies and I am about to move!" (The Glass Menagerie, 1268).

No, not that Tom.

Surprisingly, not that Tom, either. However, this may be a good opportunity to expose this secret thought of mine that I've had for the past two years -- am I the only one who thinks that Thomas Jefferson looks like Mrs. Bohn? Either I'm crazy or she should seriously look at her ancestry.

One of the questions in the book asks, "What qualities possessed by Tom, and by him alone, make him the proper narrator of the play?"

Tom seems to be the most round character in the play -- temperamental, poetic, friendly, trapped -- so I think he has the most interesting perspective. Only he could have delivered the final few lines of the play because he was the one who felt bounded by St. Louis and needed to find adventure.

An obvious answer the question is that Tom is a poet. He barely focuses on his day job and instead writes poetry; Jim calls him "Shakespeare." The ideal narrator of a play should have the poetic eloquence that Tom has.

Finally, the character list says that Tom is "not remorseless, but to escape from a trap he has to act without pity" (1234567 -- sorry, I got carried away -- 1234). Perhaps Williams wanted to have a narrator who connects with the others characters the least, and Tom fits that description well. That way, we see the characters from a relatively impartial lens instead of, say, Amanda's lens that would be very protective of Laura and critical of Tom.

No, not that Tom.

Surprisingly, not that Tom, either. However, this may be a good opportunity to expose this secret thought of mine that I've had for the past two years -- am I the only one who thinks that Thomas Jefferson looks like Mrs. Bohn? Either I'm crazy or she should seriously look at her ancestry.

One of the questions in the book asks, "What qualities possessed by Tom, and by him alone, make him the proper narrator of the play?"

Tom seems to be the most round character in the play -- temperamental, poetic, friendly, trapped -- so I think he has the most interesting perspective. Only he could have delivered the final few lines of the play because he was the one who felt bounded by St. Louis and needed to find adventure.

An obvious answer the question is that Tom is a poet. He barely focuses on his day job and instead writes poetry; Jim calls him "Shakespeare." The ideal narrator of a play should have the poetic eloquence that Tom has.

Finally, the character list says that Tom is "not remorseless, but to escape from a trap he has to act without pity" (1234567 -- sorry, I got carried away -- 1234). Perhaps Williams wanted to have a narrator who connects with the others characters the least, and Tom fits that description well. That way, we see the characters from a relatively impartial lens instead of, say, Amanda's lens that would be very protective of Laura and critical of Tom.

Thursday, January 26, 2012

Any other Iago fans?

"IAGO. She was a wight, if ever such wight were --

DESDEMONA. To do what?

IAGO. To suckle fools and chronicle small beer" (Othello, II.i.157-159).

I mean, if anything, I'm a feminist -- go, Abigail Adams and Margaret Sanger! (apparently, I need more pictures of American women in this blog) -- but this part was really funny, and not because I agree with Iago. I think I find humor in the fact that since Shakespeare's time, we haven't really made much progress in sexist jokes.

Let's identify the protagonist and antagonist. I previously mentioned that Iago is the antagonist, and I believe Othello would be considered the protagonist. And if the hero really always dies in Shakespearean tragedies -- well, sorry about your luck, Othello.

Now, let's talk about why I like Iago, which is potentially controversial.

1. Iago is an extremely round character; I mean, his character is a perfect circle. He's wicked smart and clever, he has experience serving his state, and he wants to see justice in action (at least when he's faced with the injustice, which brings me to . . .).

2. Iago has right on his side. I agree -- planning to frame and murder somebody, lie to just about everybody, and treat one's wife with childish contempt is a bit of an overreaction to not getting a desired promotion -- but gosh darn it, Iago should have been appointed lieutenant.

3. Iago makes the play interesting. Think of how crappy this story would be if Iago gave in and decided that Cassio is a worthy lieutenant.

4. Iago is telling me the story as we go along. Iago is anything but withholding, and I appreciate the fact that he's keeping me and not the other characters in the loop. It makes me feel special.

5. Iago is funny in an astutely vulgar way, as we witnessed above.

DESDEMONA. To do what?

IAGO. To suckle fools and chronicle small beer" (Othello, II.i.157-159).

I mean, if anything, I'm a feminist -- go, Abigail Adams and Margaret Sanger! (apparently, I need more pictures of American women in this blog) -- but this part was really funny, and not because I agree with Iago. I think I find humor in the fact that since Shakespeare's time, we haven't really made much progress in sexist jokes.

Let's identify the protagonist and antagonist. I previously mentioned that Iago is the antagonist, and I believe Othello would be considered the protagonist. And if the hero really always dies in Shakespearean tragedies -- well, sorry about your luck, Othello.

Now, let's talk about why I like Iago, which is potentially controversial.

1. Iago is an extremely round character; I mean, his character is a perfect circle. He's wicked smart and clever, he has experience serving his state, and he wants to see justice in action (at least when he's faced with the injustice, which brings me to . . .).

2. Iago has right on his side. I agree -- planning to frame and murder somebody, lie to just about everybody, and treat one's wife with childish contempt is a bit of an overreaction to not getting a desired promotion -- but gosh darn it, Iago should have been appointed lieutenant.

3. Iago makes the play interesting. Think of how crappy this story would be if Iago gave in and decided that Cassio is a worthy lieutenant.

4. Iago is telling me the story as we go along. Iago is anything but withholding, and I appreciate the fact that he's keeping me and not the other characters in the loop. It makes me feel special.

5. Iago is funny in an astutely vulgar way, as we witnessed above.

Wednesday, November 16, 2011

With submission, sir . . .

"So that Turkey's paroxysms only coming on about twelve o'clock, I never had to do with their eccentricities at one time. Their fits relieved each other like guards" ("Bartleby the Scrivener," 13).

Question Thirteen asks about humor, so let's talk about the humor.

I found this story a bit tedious but genuinely funny. The images of certain characters was extremely humorous to me -- it took a while for me to recover after the "guards" simile. What it does is characterizes Turkey and Nippers in a very engaging way; it also creates some sympathy for the narrator, who has to deal with exactly one ill-tempered person at a time. The little repetitive phrases like "with submission, sir" (Turkey, various moments) also served as what I thought were funny characterization methods. There are other instances like this, but let's turn to Bartleby.

There's a strong contrast between the narrator and Bartleby when the narrator asks for something to be done. For example, when the narrator first explained that Bartleby needed to help examine the copies, he did so "hurriedly" with little patience (30). Bartleby, on the other hand, always maintained composure, no matter how weird he was. There are very ironic moments where the narrator will describe how intensely hardworking Bartleby is, and then Bartleby will inconsistently be of no assistance to the narrator.

Then again, I couldn't stop laughing when I was reading the poem "Edward," so I probably have little right to speak on the subject of humor.

Question Thirteen asks about humor, so let's talk about the humor.

I found this story a bit tedious but genuinely funny. The images of certain characters was extremely humorous to me -- it took a while for me to recover after the "guards" simile. What it does is characterizes Turkey and Nippers in a very engaging way; it also creates some sympathy for the narrator, who has to deal with exactly one ill-tempered person at a time. The little repetitive phrases like "with submission, sir" (Turkey, various moments) also served as what I thought were funny characterization methods. There are other instances like this, but let's turn to Bartleby.

There's a strong contrast between the narrator and Bartleby when the narrator asks for something to be done. For example, when the narrator first explained that Bartleby needed to help examine the copies, he did so "hurriedly" with little patience (30). Bartleby, on the other hand, always maintained composure, no matter how weird he was. There are very ironic moments where the narrator will describe how intensely hardworking Bartleby is, and then Bartleby will inconsistently be of no assistance to the narrator.

Then again, I couldn't stop laughing when I was reading the poem "Edward," so I probably have little right to speak on the subject of humor.

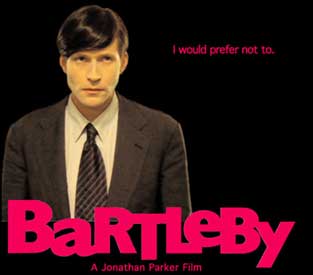

I would prefer not to analyze this story.

"The report was this: that Bartleby had been a subordinate clerk in the Dead Letter Office at Washington, from which he had been suddenly removed by a change in the administration. When I think over this rumor, I cannot adequately express the emotions which seize me. Dead letters! does it not sound like dead men?" ("Bartleby the Scrivener," 250).

Question Eight asks about Bartleby's motivation behind his behavior, Melville's motivation behind his withholding this piece of information, and the extent to which this information adequately explains Bartleby. So I'm going to answer about it!

The narrator suggests that if Bartleby were already pallidly hopeless, working in the Dead Letter Office would make him even more hopeless. If this rumor is true, which is all I can assume, then Bartleby spent a great deal of time sorting dead letters for destruction -- letters, bank notes, rings never to be delivered. Bartleby's "I would prefer not to" attitude may not be annoying as much as it is hopeless. If I lacked hope to the extent that Bartleby did, I would have trouble working as a copyist, too -- perhaps not to Bartleby's extent, but characters have to be exaggerated.

So why does Melville hold off this last piece of information? I think that Melville wants us to detest Bartleby during the story. How annoying is it that he refuses to be of any additional help to the narrator? How creepy is it that he stays in the office for abnormal amounts of time and refuses to leave even when the office is gone? Then, once we have this crucial piece of information, we might (reluctantly) develop a feeling of pity for Bartleby. It's kind of like a guilt trip, I think. We spend the entire three hours we read the story being put off by Bartleby's words and actions when we fail to consider what traumatic past he may have endured. Bartleby may seem flat on the surface but is very round on the inside. I'm not calling him fat.

This is kind of morphing into a bland theme of "don't judge someone because you don't know what his situation is." Melville says it better. Albeit much longer.

Question Eight asks about Bartleby's motivation behind his behavior, Melville's motivation behind his withholding this piece of information, and the extent to which this information adequately explains Bartleby. So I'm going to answer about it!

The narrator suggests that if Bartleby were already pallidly hopeless, working in the Dead Letter Office would make him even more hopeless. If this rumor is true, which is all I can assume, then Bartleby spent a great deal of time sorting dead letters for destruction -- letters, bank notes, rings never to be delivered. Bartleby's "I would prefer not to" attitude may not be annoying as much as it is hopeless. If I lacked hope to the extent that Bartleby did, I would have trouble working as a copyist, too -- perhaps not to Bartleby's extent, but characters have to be exaggerated.

So why does Melville hold off this last piece of information? I think that Melville wants us to detest Bartleby during the story. How annoying is it that he refuses to be of any additional help to the narrator? How creepy is it that he stays in the office for abnormal amounts of time and refuses to leave even when the office is gone? Then, once we have this crucial piece of information, we might (reluctantly) develop a feeling of pity for Bartleby. It's kind of like a guilt trip, I think. We spend the entire three hours we read the story being put off by Bartleby's words and actions when we fail to consider what traumatic past he may have endured. Bartleby may seem flat on the surface but is very round on the inside. I'm not calling him fat.

This is kind of morphing into a bland theme of "don't judge someone because you don't know what his situation is." Melville says it better. Albeit much longer.

I hate Kenny. Haha, just kidding.

"Kenny turned to Tub. 'I hate you.'

Tub shot from the waist" ("Hunters in the Snow," 79-80).

Let's synthesize the last two units! There are several instances in the story where plot and characterization work together, and important plot points are arguably a direct result of characeters' personalities.

Example One: "You Shot Me"

Kenny's character is described very richly in the beginning of the story; a huge part of his character is his inability to know where to stop a practical joke. He nearly ran over Tub on the first page of the story, but Kenny was "just messing around" (7). He provoked Frank about a secret babysitter situation, but Kenny laughed it off (22). Unsurprisingly, this got him into a wee bit of trouble. Kenny pretended to shoot a post, a tree, and a dog out of hatred (71-78). A direct result of this character trait was Tub's shooting Kenny out of personal defense (80). I had no idea it was a joke until Kenny said he was "just kidding around" again (84).

Example Two: We Don't Need Directions

The farmer gave Tub and Frank directions to the nearest hospital, but Tub left them "on the table back there" at a bar where they stopped (209). Tub's character is revealed throughout the story to be, well, not very quick in the mind. Or the body. As an ultimate result, the three characters never arrived at the hospital in time to help Kenny (239). Good work, Tub.

If I could find it, I would embed the clip of "Pirates of the Caribbean" where the guy says, "He shot me!" Just so you know.

Tub shot from the waist" ("Hunters in the Snow," 79-80).

Let's synthesize the last two units! There are several instances in the story where plot and characterization work together, and important plot points are arguably a direct result of characeters' personalities.

Example One: "You Shot Me"

Kenny's character is described very richly in the beginning of the story; a huge part of his character is his inability to know where to stop a practical joke. He nearly ran over Tub on the first page of the story, but Kenny was "just messing around" (7). He provoked Frank about a secret babysitter situation, but Kenny laughed it off (22). Unsurprisingly, this got him into a wee bit of trouble. Kenny pretended to shoot a post, a tree, and a dog out of hatred (71-78). A direct result of this character trait was Tub's shooting Kenny out of personal defense (80). I had no idea it was a joke until Kenny said he was "just kidding around" again (84).

Example Two: We Don't Need Directions

The farmer gave Tub and Frank directions to the nearest hospital, but Tub left them "on the table back there" at a bar where they stopped (209). Tub's character is revealed throughout the story to be, well, not very quick in the mind. Or the body. As an ultimate result, the three characters never arrived at the hospital in time to help Kenny (239). Good work, Tub.

If I could find it, I would embed the clip of "Pirates of the Caribbean" where the guy says, "He shot me!" Just so you know.

An "Aha Moment"

"I did something I never had done before: hugged Maggie to me, then dragged her on into the room, snatched the quilts out of Miss Wangero's hands and dumped them into Maggie's lap. Maggie just sat there on my bed with her mouth open" ("Everyday Use," 76).

Mrs. Johnson's unprecedented words and actions with Dee illustrate a major change in character -- the narrator is a dynamic character. Both Mrs. Johnson's motivation and foreshadowing throughout the story make this a fitting shift in character.

I would describe both the narrator and Maggie as "simple." Mrs. Johnson is a rough, hardworking mother, and Maggie lacks "good looks," "money," and "quickness," much like her mother (13). While Mrs. Johnson and Maggie share this special connection, Dee has developed a different "style," which the narrator passively resented (12). "No" was a word Mrs. Johnson has rarely spoken to her eldest daughter (2). That's the before situation -- there is a conflict between Dee and her mother, and I knew it would be resolved, probably by her mother finally saying that word, "no."

Several plot elements probably drove the mother to refuse to let Dee have her mother's quilts. Dee detached herself from her "oppressive" family by changing her name to "Wangero" (25). Then, she took the family's churn top, a tool both beautiful and useful to Mrs. Johnson (54). Then, when the narrator suddenly refused to allow Dee to take the quilts, Dee accused her of not understanding her heritage (81).

I attribute the narrator's sudden shift to an epiphany, and I believe that this change in character is permanent -- it fits perfectly. The narrator made a promise to Maggie (64) -- or at least said she did -- because she is legitimately closer to Maggie. Additionally, Dee's actions were inconsistent; she abandoned her family name, yet accused Mrs. Johnson of not understanding her heritage. Go, Mrs. Johnson!

Also, Big Dee (in video game form -- 0:33):

Mrs. Johnson's unprecedented words and actions with Dee illustrate a major change in character -- the narrator is a dynamic character. Both Mrs. Johnson's motivation and foreshadowing throughout the story make this a fitting shift in character.

I would describe both the narrator and Maggie as "simple." Mrs. Johnson is a rough, hardworking mother, and Maggie lacks "good looks," "money," and "quickness," much like her mother (13). While Mrs. Johnson and Maggie share this special connection, Dee has developed a different "style," which the narrator passively resented (12). "No" was a word Mrs. Johnson has rarely spoken to her eldest daughter (2). That's the before situation -- there is a conflict between Dee and her mother, and I knew it would be resolved, probably by her mother finally saying that word, "no."

Several plot elements probably drove the mother to refuse to let Dee have her mother's quilts. Dee detached herself from her "oppressive" family by changing her name to "Wangero" (25). Then, she took the family's churn top, a tool both beautiful and useful to Mrs. Johnson (54). Then, when the narrator suddenly refused to allow Dee to take the quilts, Dee accused her of not understanding her heritage (81).

I attribute the narrator's sudden shift to an epiphany, and I believe that this change in character is permanent -- it fits perfectly. The narrator made a promise to Maggie (64) -- or at least said she did -- because she is legitimately closer to Maggie. Additionally, Dee's actions were inconsistent; she abandoned her family name, yet accused Mrs. Johnson of not understanding her heritage. Go, Mrs. Johnson!

Also, Big Dee (in video game form -- 0:33):

Wednesday, November 9, 2011

No Post on Sundays

"I was always smiling when the mailman got there, and continued smiling even after he gave me the mail and I saw today wasn't the day" ("How I Met My Husband," 196).

That, Mr. Question One, is where my expectations as a reader were overturned definitively. That's not to say that there weren't elements throughout the plot that suggested the turn of events at the end of the story.

The plot structure was mostly chronological with two exceptions -- a flashback (the story of how Edie got her job) and a few subtle references to the future. For the most part, the flashback characterized Edie as common and humble (making her a sympathetic character) as she dropped out of school and started simple work (23-24). The future references, on the other hand, foreshadowed the end of the story. Phrases like "I see that now, but didn't then" (157) and "I didn't figure out till years later" (195) suggested an impending shift in Edie's life in which she would become wiser.

Another element within the plot was the slow revelation that Chris Waters was arguably very unsuitable for Edie. He was engaged to Alice (93), was not very close with her (117), and cheated on her -- without intimacy, of course (143). The simple girl, Edie, needed someone who was ready to settle down, a prerequisite Chris clearly did not meet (I originally typed "meat").

Although I did not completely expect Edie to settle down with someone other than Chris until the second-to-last page of the story, I recognize that the arrangement of the plot gave me, the reader, clues about Edie's future with not Chris but Carmichael.

That, Mr. Question One, is where my expectations as a reader were overturned definitively. That's not to say that there weren't elements throughout the plot that suggested the turn of events at the end of the story.

The plot structure was mostly chronological with two exceptions -- a flashback (the story of how Edie got her job) and a few subtle references to the future. For the most part, the flashback characterized Edie as common and humble (making her a sympathetic character) as she dropped out of school and started simple work (23-24). The future references, on the other hand, foreshadowed the end of the story. Phrases like "I see that now, but didn't then" (157) and "I didn't figure out till years later" (195) suggested an impending shift in Edie's life in which she would become wiser.

Another element within the plot was the slow revelation that Chris Waters was arguably very unsuitable for Edie. He was engaged to Alice (93), was not very close with her (117), and cheated on her -- without intimacy, of course (143). The simple girl, Edie, needed someone who was ready to settle down, a prerequisite Chris clearly did not meet (I originally typed "meat").

Although I did not completely expect Edie to settle down with someone other than Chris until the second-to-last page of the story, I recognize that the arrangement of the plot gave me, the reader, clues about Edie's future with not Chris but Carmichael.

Tuesday, August 9, 2011

"We've run out of time. We have this one-minute discussion period going on here."

"It was like when you make a move in chess and just as you take your finger off the piece, you see the mistake you've made, and there's this panic because you don't know yet the scale of disaster you've left yourself open to" (Never Let Me Go, 124).

Though I'm still bitter about the oxford comma issue, I have to admit that Ishiguro is very good at making analogies. The other one I can remember is the puddle one, which also happened in a conversation between Kathy and Ruth.

It's an interesting idea to compare a quarreling conversation to a game of chess, but it's kind of accurate. There are some moves of little consequence that are kind of like pleasantries. There are moves where you put your opponent in an unfortunate situation, which is like being on the winning side of a debate. Then there are the moves that Ishiguro described, which are like when you slip in the middle of a conversation. Also, clocks in chess are the scariest things of my life; they're kind of like the Obama-McCain town hall debate when Tom Brokaw kept cutting them off.

Both this analogy and the puddle analogy described "mistakes" Kathy made when she was conversing with Ruth, and both of them allowed Ruth to embrace her annoying, manipulative side and dominate the conversation. Their characters really don't go well together. You know what characters do go together? Kathy and Tommy. I just . . . don't . . . like . . . Ruth.

Though I'm still bitter about the oxford comma issue, I have to admit that Ishiguro is very good at making analogies. The other one I can remember is the puddle one, which also happened in a conversation between Kathy and Ruth.

It's an interesting idea to compare a quarreling conversation to a game of chess, but it's kind of accurate. There are some moves of little consequence that are kind of like pleasantries. There are moves where you put your opponent in an unfortunate situation, which is like being on the winning side of a debate. Then there are the moves that Ishiguro described, which are like when you slip in the middle of a conversation. Also, clocks in chess are the scariest things of my life; they're kind of like the Obama-McCain town hall debate when Tom Brokaw kept cutting them off.

Both this analogy and the puddle analogy described "mistakes" Kathy made when she was conversing with Ruth, and both of them allowed Ruth to embrace her annoying, manipulative side and dominate the conversation. Their characters really don't go well together. You know what characters do go together? Kathy and Tommy. I just . . . don't . . . like . . . Ruth.

Monday, August 8, 2011

Beyond Hailsham: "A Fantasy Land"

"This might all sound daft, but you have to remember that to us, at that stage in our lives, any place beyond Hailsham was like a fantasy land; we had only the haziest notions of the world outside and about what was and wasn't possible there" (Never Let Me Go, 66).

There's a structural thing in the chapters that's been bugging me (besides the sub-par grammar, I mean). The book, so far, has been based on a bunch of interconnected anecdotes and hasn't been one fluid story, which is fine. But every time Ishiguro introduces a new anecdote, he puts this at the end of the previous one: "And all of that changed the one time that [some person] and I [past tense activity]." Then, there's a line break and the next anecdote starts. I suppose it's nice that there's a pattern.

I'm not complaining about the anecdotes themselves, though. They're doing a good job of slowly creating a world about which I know very little but increasingly more.

I haven't decided yet if the world is a kind-of-utopia like in Brave New World. Miss Lucy's character has kind of been acting as a window into the secret world around the students -- apparently smoking for them was worse than smoking for her (68). Also, like in Brave New World, the characters can't have babies (73).

In Brave New World in your pants, the characters all knew about the mysterious world, and the reader was slowly introduced to it. I like the difference in Never Let Me Go in that we're kind of learning about the "fantasy land" at the same speed as the characters; it makes me feel more included in the book.

There's a structural thing in the chapters that's been bugging me (besides the sub-par grammar, I mean). The book, so far, has been based on a bunch of interconnected anecdotes and hasn't been one fluid story, which is fine. But every time Ishiguro introduces a new anecdote, he puts this at the end of the previous one: "And all of that changed the one time that [some person] and I [past tense activity]." Then, there's a line break and the next anecdote starts. I suppose it's nice that there's a pattern.

I'm not complaining about the anecdotes themselves, though. They're doing a good job of slowly creating a world about which I know very little but increasingly more.

I haven't decided yet if the world is a kind-of-utopia like in Brave New World. Miss Lucy's character has kind of been acting as a window into the secret world around the students -- apparently smoking for them was worse than smoking for her (68). Also, like in Brave New World, the characters can't have babies (73).

In Brave New World in your pants, the characters all knew about the mysterious world, and the reader was slowly introduced to it. I like the difference in Never Let Me Go in that we're kind of learning about the "fantasy land" at the same speed as the characters; it makes me feel more included in the book.

Monday, August 1, 2011

I like polo shirts, too.

"Laura kept up her performance all through the team-picking, doing all the different expressions that went across Tommy's face: the bright eager one at the start; the puzzled concern when four picks had gone by and he still hadn't been chosen; the hurt and panic as it began to dawn on him what was really going on" (Never Let Me Go, 9).

Never Let Me Go in your pants, and I'll never let you go in mine.

I think what's going on in this quote is a bit of imagery -- I can fairly well picture the expressions on both Laura's face and Tommy's face. First, the images characterized Laura and Tommy for me. Laura is a girl who has the nerve to sit inside of a safe pavilion and make fun of somebody else. Tommy is a boy who has a fairly malleable temperament.

The imagery also showcased the pretty quick progression in Tommy's mood as he realized what was going on. At first, I was thinking, "Hey! He has a polo shirt. He must be cool." But then he started playing football and had a huge tantrum, so I couldn't relate to him much after that.

I haaave two comparisons to make. First, the sports pavilion reminded me of the humming pole at St. Mark (the place where people like me would go to, you know, observe recess rather than take part in it). Also, the part where Kathy said, "At first I thought this was just the drugs . . ." reminded me of soma. I worked hard to find a Brave New World connection, and that's all I got so far. I mean, the first part of chapter one left a lot of questions in my head, and that happened a lot in Brave New World, too.

Never Let Me Go in your pants, and I'll never let you go in mine.

I think what's going on in this quote is a bit of imagery -- I can fairly well picture the expressions on both Laura's face and Tommy's face. First, the images characterized Laura and Tommy for me. Laura is a girl who has the nerve to sit inside of a safe pavilion and make fun of somebody else. Tommy is a boy who has a fairly malleable temperament.

The imagery also showcased the pretty quick progression in Tommy's mood as he realized what was going on. At first, I was thinking, "Hey! He has a polo shirt. He must be cool." But then he started playing football and had a huge tantrum, so I couldn't relate to him much after that.

I haaave two comparisons to make. First, the sports pavilion reminded me of the humming pole at St. Mark (the place where people like me would go to, you know, observe recess rather than take part in it). Also, the part where Kathy said, "At first I thought this was just the drugs . . ." reminded me of soma. I worked hard to find a Brave New World connection, and that's all I got so far. I mean, the first part of chapter one left a lot of questions in my head, and that happened a lot in Brave New World, too.

Tuesday, July 5, 2011

Bokanovskified Zippicamiknicks

"'Oh, for Ford's sake,' said Lenina, breaking her stubborn silence, 'shut up!'" (Brave New World, 187).

Lenina and Fanny have had arguments in the book, but the whole silent treatment followed by "shut up" was new. This quote kind of made me want to take back what I said about Lenina earlier. Sorry, Lenina, you're not a total dope. You're only a little bit dopey because society forced it upon you.

I suppose we could call Lenina a dynamic character at this point. She, like few others in the civilized world, fell in love with one person. The connection between Lenina and John lacks what I would call a reasonable foundation, but it makes her stand out among her peers.

Also, I really liked when John thought to himself, "The murkiest den, the most opportune place, the strongest suggestion our worser genius can, shall never melt mine honour into lust" (192). It's hard to explain why I like that quote so much. Overall, it's just a very good sentence.

Even though this book can be stressful, I really like the words Huxley invented. So . . . that's the title of this post.

Lenina and Fanny have had arguments in the book, but the whole silent treatment followed by "shut up" was new. This quote kind of made me want to take back what I said about Lenina earlier. Sorry, Lenina, you're not a total dope. You're only a little bit dopey because society forced it upon you.

I suppose we could call Lenina a dynamic character at this point. She, like few others in the civilized world, fell in love with one person. The connection between Lenina and John lacks what I would call a reasonable foundation, but it makes her stand out among her peers.

Also, I really liked when John thought to himself, "The murkiest den, the most opportune place, the strongest suggestion our worser genius can, shall never melt mine honour into lust" (192). It's hard to explain why I like that quote so much. Overall, it's just a very good sentence.

Even though this book can be stressful, I really like the words Huxley invented. So . . . that's the title of this post.

Monday, July 4, 2011

I made it to my favorite integeeer!

"But the Director's face, as he entered the Fertilizing Room with Henry Foster, was grave, wooden with severity" (Brave New World, 147).

"But the Director's face, as he entered the Fertilizing Room with Henry Foster, was grave, wooden with severity" (Brave New World, 147).Obviously, at this point, the Director was not happy with Bernard. I'm wondering right now if there's a word for the opposite of personification, because that's basically what this is. Huxley took a non-human characteristic ("wooden") and endowed it upon a human. Antianthropomorphism, probably. Or maybe it's one of those implied metaphors. The Director is being implicitly compared to . . . a log. Whatever we want to call it, the Director was effectively portrayed as motionless and stern.

Also in chapter ten, there were multiple times when Bernard spoke either "absurdly too loud" or "ridiculously soft" (148). I can sympathize with this completely. Speaking volume is extremely complicated for some people. Anyway, this was consistent with Bernard's character -- awkward.

Sunday, July 3, 2011

Past the Halfway Point

"'As far back as I can remember.' John frowned. There was a long silence" (Brave New World, 123).

What would have been nice right after that sentence is an extra line break. It took me a page to understand that at that moment, I had entered a flashback. The flashback gave an excellent characterization of John and mostly dealt with his tragic background. There are two primary observations that I made.

First, as I was reading, I noticed a lot of stress on how much of an outcast John was during his childhood, and it reminded me of how Bernard is also an outsider in "the Other Place" (127). I was going to make a really impressive connection between the two characters in this blog, but then it got less impressive when Bernard commented about how similar they are -- "terribly alone" (137). So that's disappointing, but I suppose it's good that I caught on to their connection before that moment.

Also, I mentioned in my last post that I thought the theme would concern individualism, and I'm sticking with that, but I have another idea. This quote is back from chapter four:

"'Words can be like X-rays, if you use them properly -- they'll go through anything'" (70).

I held on to that quote because I liked it, and now I think it resonates well with John's past. Whenever John read something, he was in total awe by the "magic" (132) of words. I think the fashioning of words could also be an integral theme; additionally, words are a powerful way to express individualism, so that's pretty great.

I need . . . a picture . . . hmm . . . words are like X-rays.

What would have been nice right after that sentence is an extra line break. It took me a page to understand that at that moment, I had entered a flashback. The flashback gave an excellent characterization of John and mostly dealt with his tragic background. There are two primary observations that I made.

First, as I was reading, I noticed a lot of stress on how much of an outcast John was during his childhood, and it reminded me of how Bernard is also an outsider in "the Other Place" (127). I was going to make a really impressive connection between the two characters in this blog, but then it got less impressive when Bernard commented about how similar they are -- "terribly alone" (137). So that's disappointing, but I suppose it's good that I caught on to their connection before that moment.

Also, I mentioned in my last post that I thought the theme would concern individualism, and I'm sticking with that, but I have another idea. This quote is back from chapter four:

"'Words can be like X-rays, if you use them properly -- they'll go through anything'" (70).

I held on to that quote because I liked it, and now I think it resonates well with John's past. Whenever John read something, he was in total awe by the "magic" (132) of words. I think the fashioning of words could also be an integral theme; additionally, words are a powerful way to express individualism, so that's pretty great.

I need . . . a picture . . . hmm . . . words are like X-rays.

Thursday, June 16, 2011

We're different, different as can be!

"'Damn, I'm late,' Bernard said to himself as he first caught sight of Big Henry, the Singery clock" (Brave New World, 78).

I was wary of saying this in my last post, but now that I've read chapter five, I'm more confident about it. (Deep breath.) It seems to me that Bernard Marx and Henry Foster are foil characters.

Already, I've placed them into two different mental groups -- Bernard is an outsider with an unconventional thought process while Henry is stuck with his hypnopaedic views. The way they act also plays along with this; Bernard is really awkward and Henry is a hit with the ladies. Now I also know that, unlike the extremely punctual Henry, Bernard was late to his Solidarity Service. (I'm not even going to talk about how creepy that whole part was.)

Just now, I'm piecing together possible implications of their names. "Henry Foster," I noticed from his first appearance, is remarkably close to "Henry Ford." Ford was as American, consumeristic, and free markety as anyone can get. Bernard Marx shares his last name with Karl Marx, who made huge contributions to the ideas of socialism and communism. So even their names are strongly contrasted with one another.

The sharp differences between Henry and Bernard really highlight their distinct personalities. Umm, and they make me like Bernard more than I like Henry.

I was wary of saying this in my last post, but now that I've read chapter five, I'm more confident about it. (Deep breath.) It seems to me that Bernard Marx and Henry Foster are foil characters.

Just now, I'm piecing together possible implications of their names. "Henry Foster," I noticed from his first appearance, is remarkably close to "Henry Ford." Ford was as American, consumeristic, and free markety as anyone can get. Bernard Marx shares his last name with Karl Marx, who made huge contributions to the ideas of socialism and communism. So even their names are strongly contrasted with one another.

The sharp differences between Henry and Bernard really highlight their distinct personalities. Umm, and they make me like Bernard more than I like Henry.

Wednesday, June 15, 2011

Huxley is going to get less wordy.

"'Isn't it beautiful!' His voice trembled a little.

"She smiled at him with an expression of the most sympathetic understanding. 'Simply perfect for Obstacle Golf,' she answered rapturously" (Brave New World, 59).

All of the math in that picture is wrong because there are eighteen chapters -- not nineteen -- but you get the spirit of it.

Most of the characters in Brave New World are indirectly characterized, and their appearances and speech reveal who they are. The only exception so far is Benito Hoover who is characterized directly as "notoriously good-natured" (60), probably because he's minor.

I think there are two groups we can assign to these characters.

One group would contain people with "a mental excess" (67) like Bernard Marx and Helmholtz Watson. According to Huxley, these two share the "knowledge that they are individuals" -- they're outsiders. For this reason, I think that they're going to be dynamic in moving the plot forward.

The other group would contain everyone else -- the Director, the students, Henry Foster, Lenina, Fanny, and Benito. These people conform to the customs of their world because they have no other choice. Hypnopaedia gives the vast majority of characters ideas and prejudices they cannot escape on their own. Maybe the people in Group One will help them out, but I don't think these characters can make an interesting story on their own.

The quote I chose for this post shows the fascinating and almost comical boundary between these two groups. As Bernard finds true beauty in the sky, Lenina "understands" him and agrees that it's good weather to play golf. I think this is dramatic irony because Lenina thinks she's sympathizing with Bernard when the reader knows that the kinds of beauty the two characters see are completely different.

"She smiled at him with an expression of the most sympathetic understanding. 'Simply perfect for Obstacle Golf,' she answered rapturously" (Brave New World, 59).

All of the math in that picture is wrong because there are eighteen chapters -- not nineteen -- but you get the spirit of it.

Most of the characters in Brave New World are indirectly characterized, and their appearances and speech reveal who they are. The only exception so far is Benito Hoover who is characterized directly as "notoriously good-natured" (60), probably because he's minor.

I think there are two groups we can assign to these characters.

One group would contain people with "a mental excess" (67) like Bernard Marx and Helmholtz Watson. According to Huxley, these two share the "knowledge that they are individuals" -- they're outsiders. For this reason, I think that they're going to be dynamic in moving the plot forward.

The other group would contain everyone else -- the Director, the students, Henry Foster, Lenina, Fanny, and Benito. These people conform to the customs of their world because they have no other choice. Hypnopaedia gives the vast majority of characters ideas and prejudices they cannot escape on their own. Maybe the people in Group One will help them out, but I don't think these characters can make an interesting story on their own.

The quote I chose for this post shows the fascinating and almost comical boundary between these two groups. As Bernard finds true beauty in the sky, Lenina "understands" him and agrees that it's good weather to play golf. I think this is dramatic irony because Lenina thinks she's sympathizing with Bernard when the reader knows that the kinds of beauty the two characters see are completely different.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)