"Just as Mr. Summers finally left off talking and turned to the assembled villages, Mrs. Hutchinson came hurriedly along the path to the square, her sweater thrown over her shoulders, and slid into place in the back of the crowd" (266).

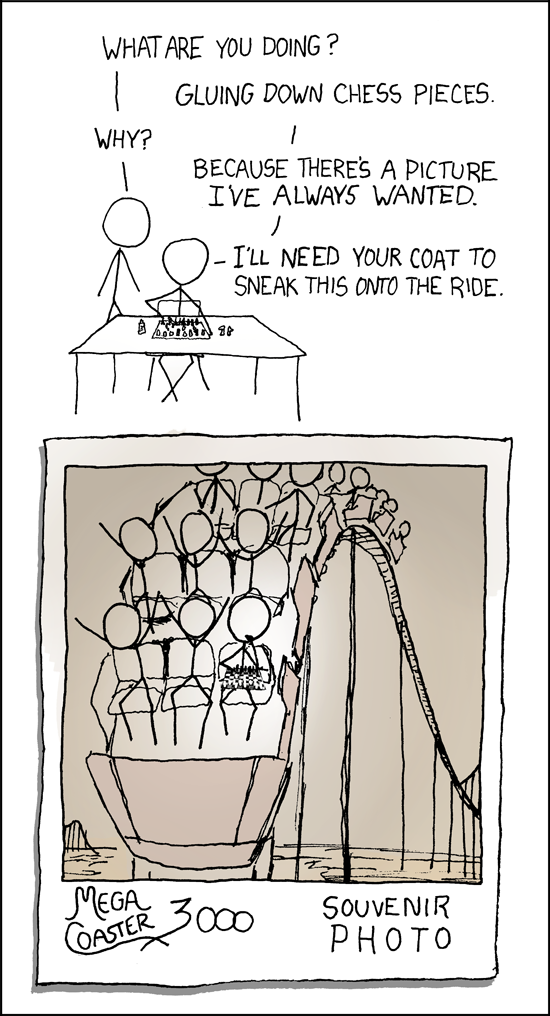

All right, Perrine, you're asking for it; I've whipped out math in blogs before this one, and I'm not afraid to do it again. I quote the third question. "What normal law of probability has been suspended in this story? Granting this initial implausibility, does the story proceed naturally?"

At first, I wasn't sure what Perrine was talking about, but then I had a little epiphany. Perrine wants to know what happened during the lottery that was implausible. For Perrine, I have two answers, and then I will explode on him.

First, Old Man Warner is "the oldest man in town" (5). Some people might find it odd that someone as old as Old Man Warner would have survived the lottery every year of his life and classify that as "implausible." Second, Tessie Hutchinson was the one person who showed up late to the lottery, and it just so happened that she was the . . . winner (77-79). Is that at all likely?

My first objective in this post is to determine the plausibility of these two scenarios. I'm going to make two assumptions so I can do the math: the population of this village has remained constant at 300 people during Old Man Warner's entire life, and Old Man Warner (OMW, for short) is 150 years old (a generously high age).

- The probability of OMW's survival of the lottery for his entire life is (299/300)^150, or about a 60.6% chance.

- The probability of Tessie's death as the sole latecomer is simply (1/300), or about a 0.3% chance.

- The probability of any person winning the lottery is also (1/300), or about a 0.3% chance.

Certainly, the more implausible case of the first two is the second one -- it's extremely unlikely that the sole latecomer to the lottery would be the winner. Surprisingly, it's somewhat likely that someone can live to be 150 years old without winning the lottery in the village.

My second objective in this post is to say this very clearly. NO NORMAL LAW OF PROBABILITY HAS BEEN SUSPENDED, AND YOUR SENTENCE USES PASSIVE VOICE. I feel very strongly about this. Just because it was unlikely that Tessie (the only person who came late) would be stoned does not mean that a law of probability was suspended. The laws of probability always stand, even when the most likely outcome does not occur.

Unless someone can convince me that Perrine was referring to some other rule of probability, I will remain angry at him. Perrine, you stick to literature, and I'll stick to math, and we won't have to cross each other anymore once I finish this class.